How to Read a Building

The University of Minnesota’s historic Pillsbury Hall, recently renovated by Architecture Advantage, can be read on multiple levels

By Thomas Fisher, Assoc. AIA | September 23, 2021

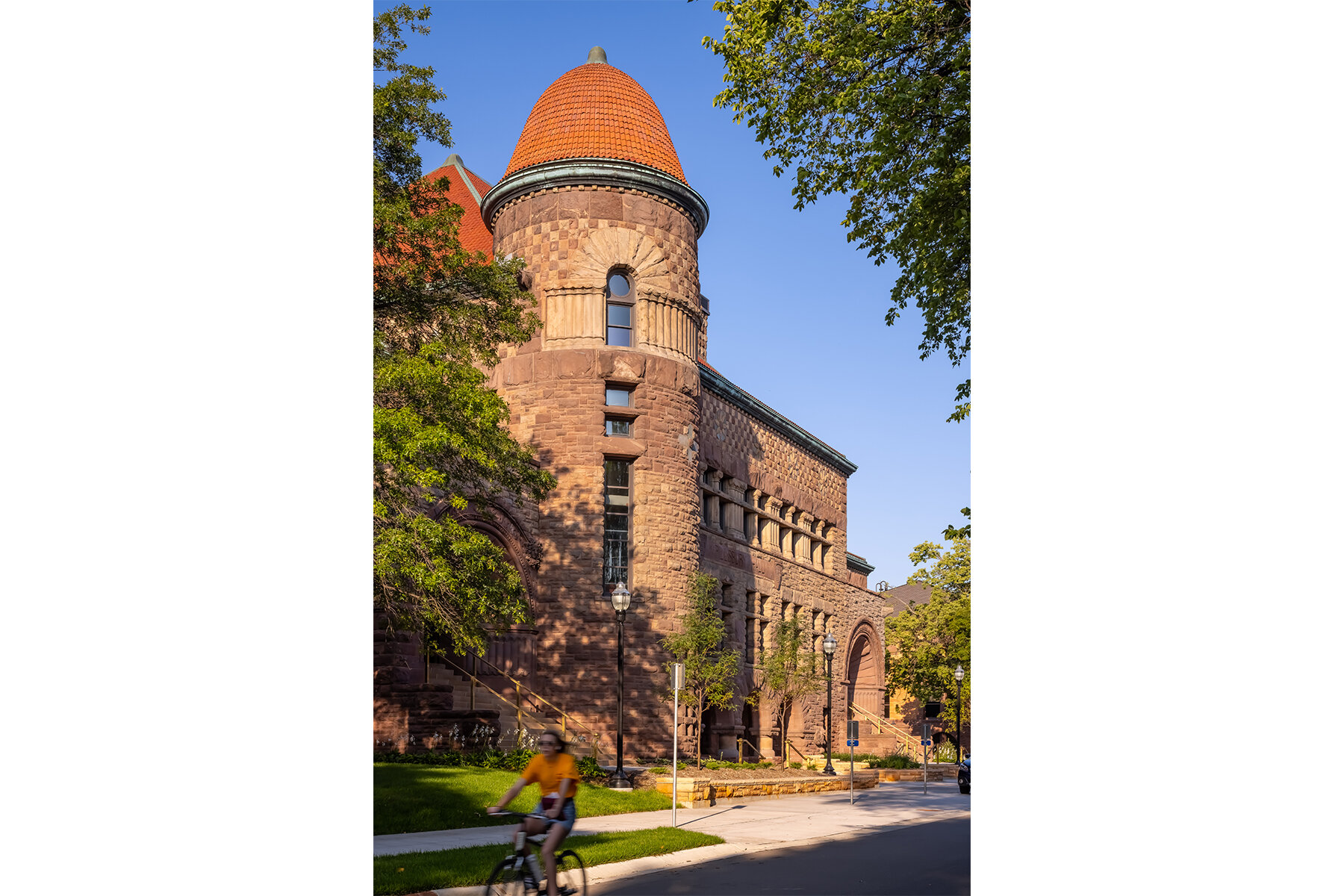

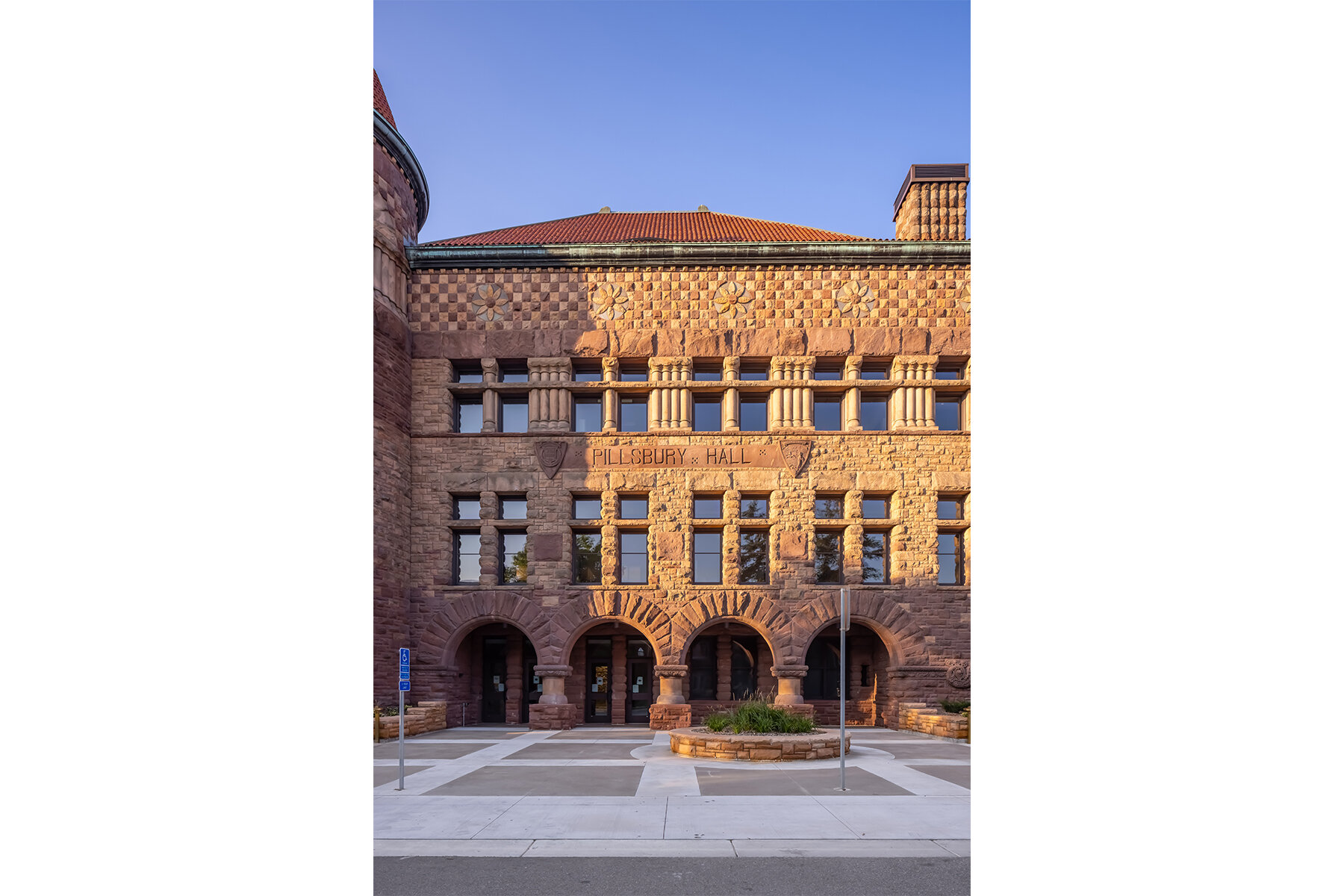

Morning light on the newly rejuvenated Pillsbury Hall, at the heart of the University of Minnesota’s East Bank campus. All photos by Farm Kid Studios.

FEATURE

With the move of the University of Minnesota’s renowned English Department and Creative Writing Program into one of the most distinguished buildings on campus, Pillsbury Hall, it seems fitting to think about the relationship of books and buildings, and how best to read both. Early in my own education, I read Mortimer Adler’s How to Read a Book, which seemed paradoxical, since it assumed that the reader already knew how to read a book in order to read a book about how to read a book. But Adler’s work remains a valuable guide to help us read not only books but also buildings like Pillsbury Hall.

Adler called the basic ability of a literate person to read a book “elementary reading,” and that applies to reading a building like Pillsbury as well. Designed by Minneapolis architect Leroy Buffington and his talented assistant Harvey Ellis, completed in 1889, and paid for in part by the state legislature and in part by former governor John S. Pillsbury, the building has the simple, oversized quality of a children’s book, with exaggerated features like overly tall windows, extra-thick stone walls, and super-wide arches, all beneath a massive tile roof. It’s an easy-to-read building that is also easy on the eyes.

Pillsbury Hall offers a rich reading experience both up close and from a distance. All photos by Farm Kid Studios.

Upon closer look—in what Adler called “inspectional reading”—Pillsbury Hall also has more than meets the eye. Adler advocated the “intelligent skimming” of a book’s table of contents and index and the “superficial reading” of sections of a book that initially seem most interesting. We can do the same inspectional reading of a building like Pillsbury. Skimming its facade, we can see that, in addition to the original entrances up long flights of stairs, the building now has an accessible entrance off a new front plaza. In general, the more easily people can get into a building—or a book—the better.

A superficial reading of Pillsbury Hall also gives us much to look at. In addition to its completely renovated interior (see sidebar below), the building has a recently cleaned and restored exterior full of appealing details: red and buff-colored sandstone walls; red-tile, copper-trimmed roofs; and arches upon arches that seem, well, playfully arch. Like Mark Twain’s medieval spoof, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, completed the same year as Pillsbury Hall, the latter has several medieval motifs, including a chimera (part lion, part serpent) and a medusa head (with serpents as hair) carved into its brownstone trim. The carvings bestow both wild imagination and willpower upon all who enter the building.

HIGH MARKS

This fall, the University of Minnesota Department of English welcomed 6,000 undergraduate and graduate students into its new—and newly revitalized—home in Pillsbury Hall. A nearly two-year renovation by Architecture Advantage transformed 62,500 square feet of obsolete space into contemporary environments designed for multiple modes of learning, alternative workplace, non-laboratory research, and scholarship. Throughout the project, the Architecture Advantage design team balanced rigid adherence to standards for the historic exterior with interior planning focused on flexibility.

Notable features of the renovation include the creation of an accessible new main entrance and entry plaza, the insertion of a four-level staircase into the building’s iconic tower, and the conversion of attic storage space into a large lecture hall with a vaulted ceiling. The design for the lecture hall ingeniously incorporates the roof’s original framing. As a state-funded project, the renovation had to meet the State of Minnesota’s Sustainable Building 2030 (SB 2030), a nation-leading energy standard for public buildings. Architecture Advantage and its project partners did so in part with the use of chilled-beam technology and by insulating the roof from the interior to avoid interfering with the historic roof tiles.

The Pillsbury Hall project team also included JE Dunn, Good Clancy, BKBM, IMEG Corp., M-P Consultants, Loucks, and True North.

Much of what the English Department teaches in Pillsbury Hall is what Adler called “analytical” reading to understand the subject, substance, and structure of written work. Like that of a book, the subject of a building like Pillsbury rarely changes: Pillsbury has remained an academic building, even though its use and interpretation have changed over time (originally designed for the sciences, it now houses one of the humanities). We could say the same of its substance and structure. The substantial quality of Pillsbury Hall’s stone walls gives the building a literal and figurative weight that defies anyone who might tear it down. And the straightforward structure of the building—two wings extending to either side of a tall, central block, with a round stair tower announcing itself next to the main entrance—gives it a clarity and generosity that have helped it accommodate changing academic needs for over 130 years.

Which brings us to Adler’s final category: the “syntopical” reading of a book, where we read many works of a similar type or on the same subject and compare and contrast them. That process lies at the heart of scholarship, whether we’re reading books or buildings. Our region has several buildings of Pillsbury Hall’s ilk, like Minneapolis’s City Hall, which broke ground the year of Pillsbury’s completion, and Duluth’s old Central High School, finished three years after Pillsbury. Deploying an especially forceful version of Romanesque architecture popularized by the Boston architect Henry Hobson Richardson, these massive, neo-medieval piles expressed the widespread, late-19th-century belief in the power of human organization and individual effort to achieve great things—like moving mountains of stone to construct such buildings.

We now know what that optimistic individualism left out or covered over: the lives shortened by poor living and working conditions, the air polluted by unregulated industries, and the growing wealth gap between people like Pillsbury and those who labored to construct this building in his name. A syntopical reading of a building, like that of a book, can reveal the unseen and unspoken. John S. Pillsbury liked to say that we should “act for the greatest good,” and although we might now ask, “for whom?” we can say that, in the case of Pillsbury Hall, great good has come from his gift.