The Bell Museum Is a Diorama of the Natural World

Sustainable design and environmental learning tools merge in the architecture and landscape of the award-winning natural history museum

By Amy Goetzman | May 6, 2021

The east entrance, reserved for the arrival of busloads of children. Photo by Peter J. Sieger.

FEATURE

The evidence is mounting, and the message is clear: We’ve got to do better by this planet. Human activities are altering the environment beyond its ability to repair itself and pushing species in every classification of living things to the brink of extinction. Some species are already gone and are archived in the Bell Museum’s specimen collections. But Minnesota’s preeminent natural history museum doesn’t linger on what we have lost; instead, it’s helping to save the planet by inspiring appreciation for Earth’s living wonders.

In its new Perkins&Will–designed building on the University of Minnesota’s St. Paul Campus, the Bell Museum tells the stories of the creatures and landscapes that make Minnesota unique. Time stands still in the Bell’s famous artistic dioramas—some a century old—which are restored and shine in the new building. But the energy of living beings now permeates the museum experience.

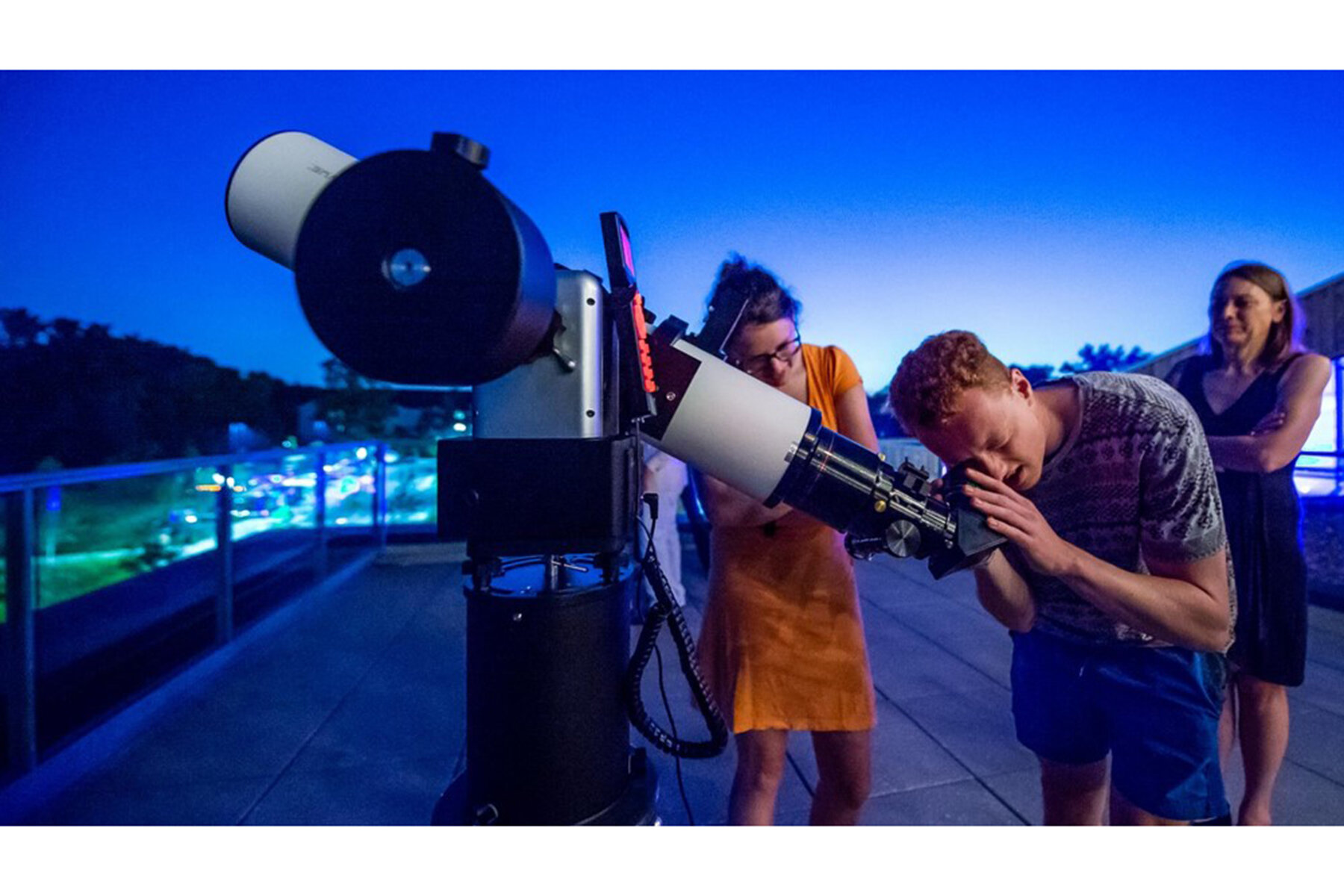

At the Bell Museum, environmental learning opportunities are up close and hands on. Photos by Joe Szurszewski.

It all starts outside, where the Bell’s multilayered Learning Landscape transcends mere gardens and grounds to demonstrate aquatic communities (and smart water management), native plantings (low maintenance and pollinator-friendly), biodiversity (living birds beat taxidermy), and environmental beauty (nature can thrive, even in the city). Three years after its opening, the new habitat attracts diverse bird, insect, and mammal species, including humans, across the five-acre site.

“We view our Learning Landscape as a front yard that allows people to get acquainted with the Bell, and also as a gateway not only to the St. Paul campus but to research done at the university, across all of its campuses,” says Jennifer Stampe, associate director of public engagement and science learning. “Interpretation in the landscape ties to stories in our permanent galleries that foreground what’s special in Minnesota, including our geology and topography, the native species and ecosystems here, and the convergence of prairie grassland, deciduous forest, and coniferous forest biomes.”

Time stands still in the Bell’s famous artistic dioramas—some a century old—which are restored and shine in the new building. But the energy of living beings now permeates the museum experience.

The Learning Landscape has turned out to be exceptionally important during the pandemic; it’s getting a lot of use as a safe space for natural exploration away from home, says Stampe. Even when the museum is closed, neighbors and students interact with it, monitoring the frog pond, nesting sites, and pollinator and rain gardens and reporting on the changes they observe as the seasons pass and the habitat matures.

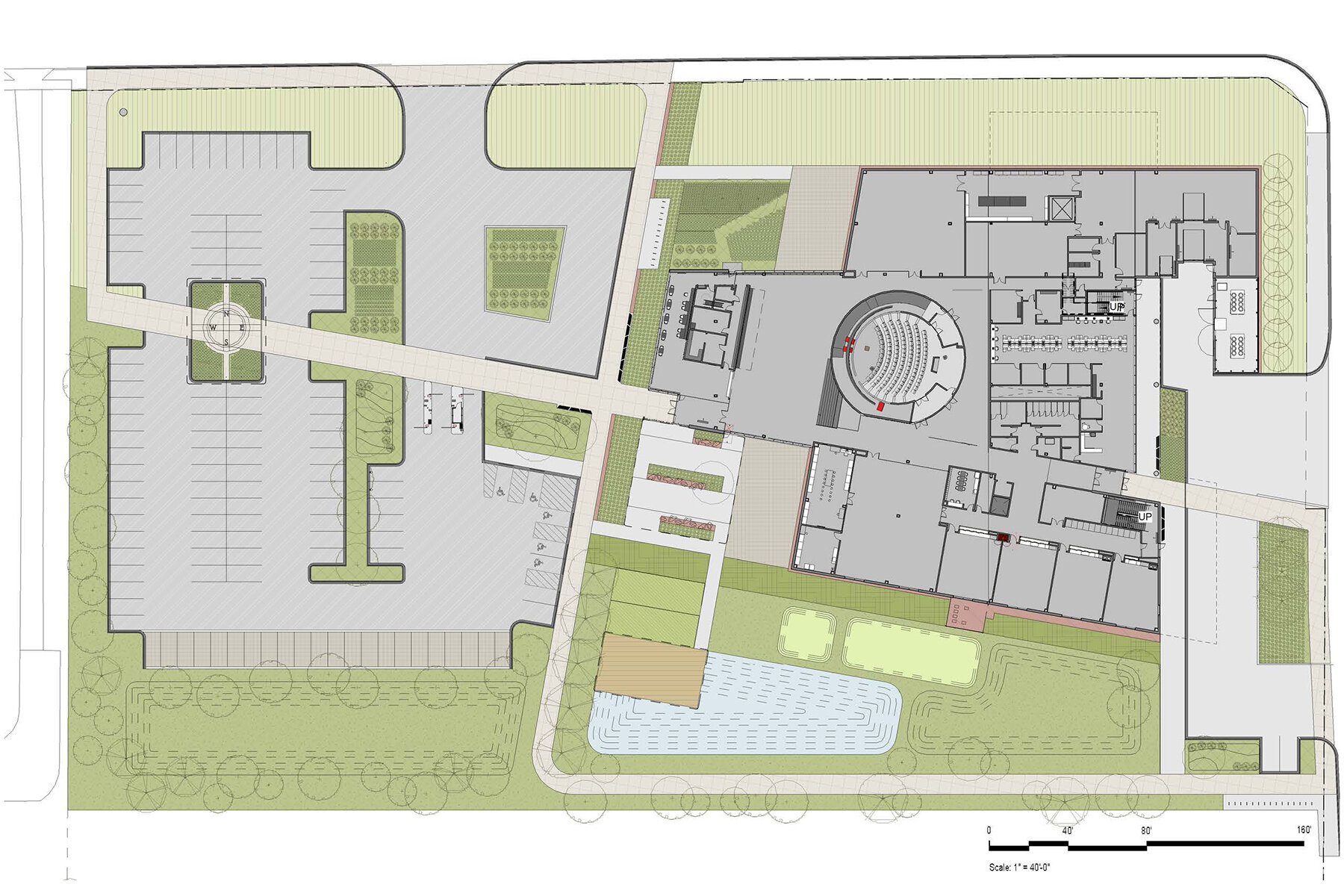

The building’s sustainably sourced materials from local suppliers include granite from Morton, white pine from Cass Lake, bird-friendly glass from Owatonna, and multiple forms of steel produced from the Iron Range. Photos by Peter J. Sieger. Site plan by Perkins&Will.

The landscape also expands the Bell’s programming. “This summer, we’re excited to host the exhibition ‘Bugs: Outside the Box,’ featuring 16 artist sculptures of arthropods at a scale of 20 times larger than life,” says Stampe. “At its core, the exhibition is an exploration of the power of close observation. But outside, we’ll be giving visitors a chance to get up close and personal with native bugs through activities that draw on some of the central sustainability features of the Learning Landscape.”

The 90,000-square-foot building is an active part of the ecosystem as well, with its green roof, Minnesota materials, and other environmentally friendly features. “One hundred percent of the exterior glazing uses a bird-safe frit pattern that is very effective while having only a minimal impact on views through the glass,” says Doug Bergert, AIA, senior project designer at Perkins&Will. “A number of those patterns are dense enough that they actually reduce the solar heat gain into the building—and thus the energy necessary to cool the building. We collaborated with our mechanical engineers to incorporate those frit patterns into their energy model.”

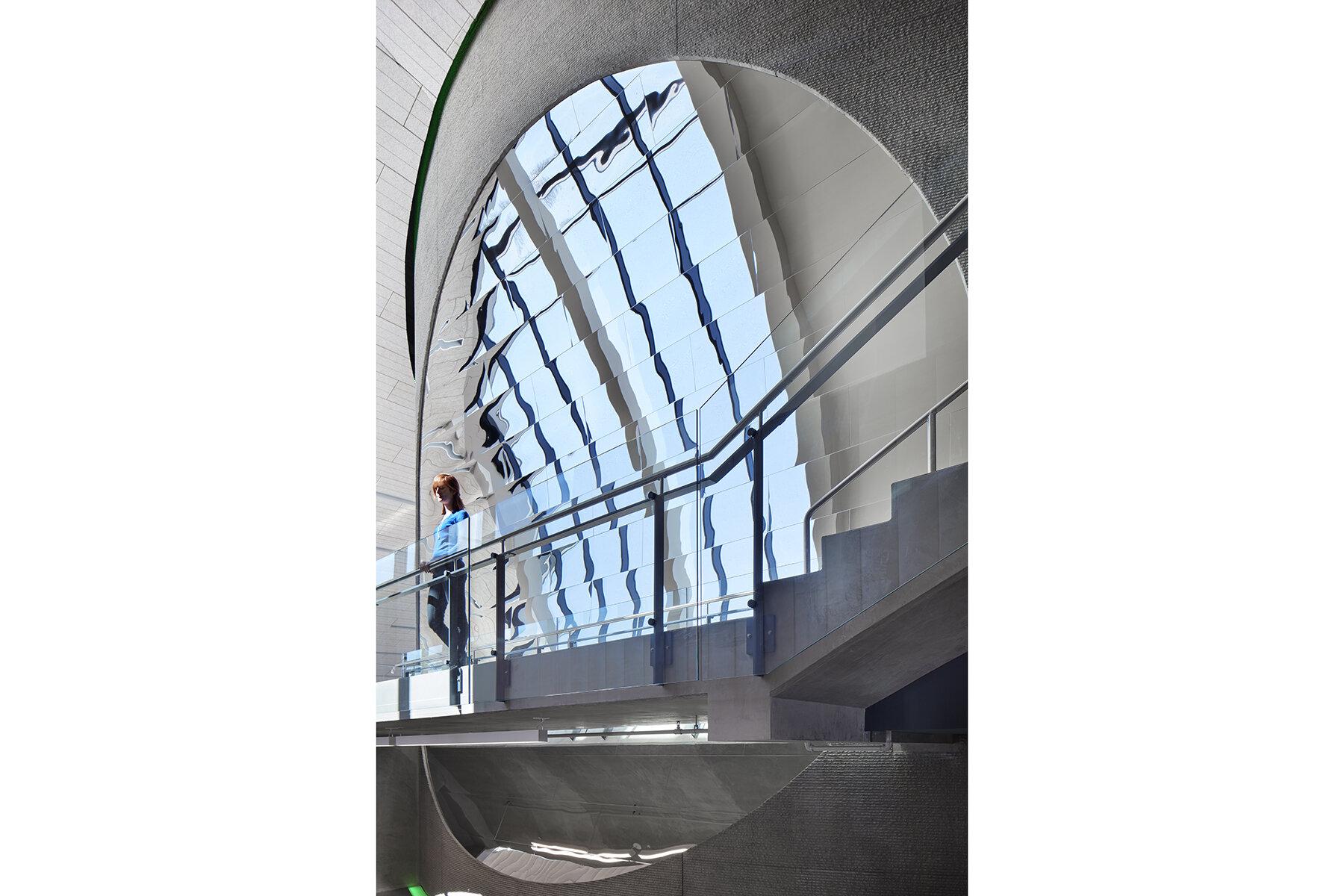

Natural light and views abound in the Bell Museum—except in the state-of-the-art planetarium. Photos by Gaffer Photography.

The museum is clad in simple, locally sourced materials that will age organically. Weathered steel oxidizes day by day. FSC-certified wood cladding made from trees responsibly harvested in northern Minnesota is minimally finished; in places, you can see the raw marks of the sawblade. Time and the elements will continue the job. “When the thermally modified boards went up on the building, the wood was a kind of warm, buttery color,” says Bergert. “Over time, it has weathered to a soft gray.”

Simplicity carries through the interior, putting the focus on the exhibits rather than the architecture. Yet the finishes also support the environmental mission and natural aesthetic. Throughout most of the museum, for example, the floor is polished concrete. “It’s just your typical cast-in-place concrete floor, polished,” says Bergert. “But it’s like running rocks through a rock polisher: You can take something kind of crude and make it almost luminous.”

Last fall, the Bell’s building and landscape design earned the museum and its architects a prestigious AIA Minnesota Honor Award, a program that celebrates achievements in the AIA Framework for Design Excellence. The 2020 AIA Minnesota Honor Award jury lauded the Bell Museum for its design in five Framework categories: Integration, Ecosystems, Water, Resources, and Change.

In addition to carrying out the Bell’s longstanding educational mission, this living museum supports research on amphibians, native bumblebee species, entomophagy (the practice of eating insects) and its potential role in space exploration, and even sustainable groundskeeping. The U has extended native plantings to other parts of the campus and developed safe deicing for the Bell’s parking lot.

Perhaps the Bell Museum’s main lesson is this: Every decision has an impact on the environment, and decisions to do right by people and other living things can be expressed in the most engaging of ways.

The Bell Museum project team included the University of Minnesota, Perkins&Will, Palanisami & Associates, Michaud Cooley Erickson, Pierce Pini + Associates, McGough, Gallagher & Associates, Kvernstoen, Rönnholm, and Associates, and Evans & Sutherland.