Macalester College’s David Wheaton on Designing for Flexibility

The school’s VP of Administration and Finance shares insights from the award-winning, three-phase transformation of the Janet Wallace Fine Arts Center

Interview by the ENTER team | April 29, 2021

David Wheaton outside the Janet Wallace Fine Arts Center. Photo by Chad Holder.

FEATURE

In 2009, Macalester College in St. Paul set about an ambitious project: converting its early 1960s arts complex from a tired masonry-and-concrete bunker into an inviting, light-filled campus crossroads teeming with creativity indoors and out. Over the next decade, the school carried out the renovation and expansion of the Janet Wallace Fine Arts Center in three phases.

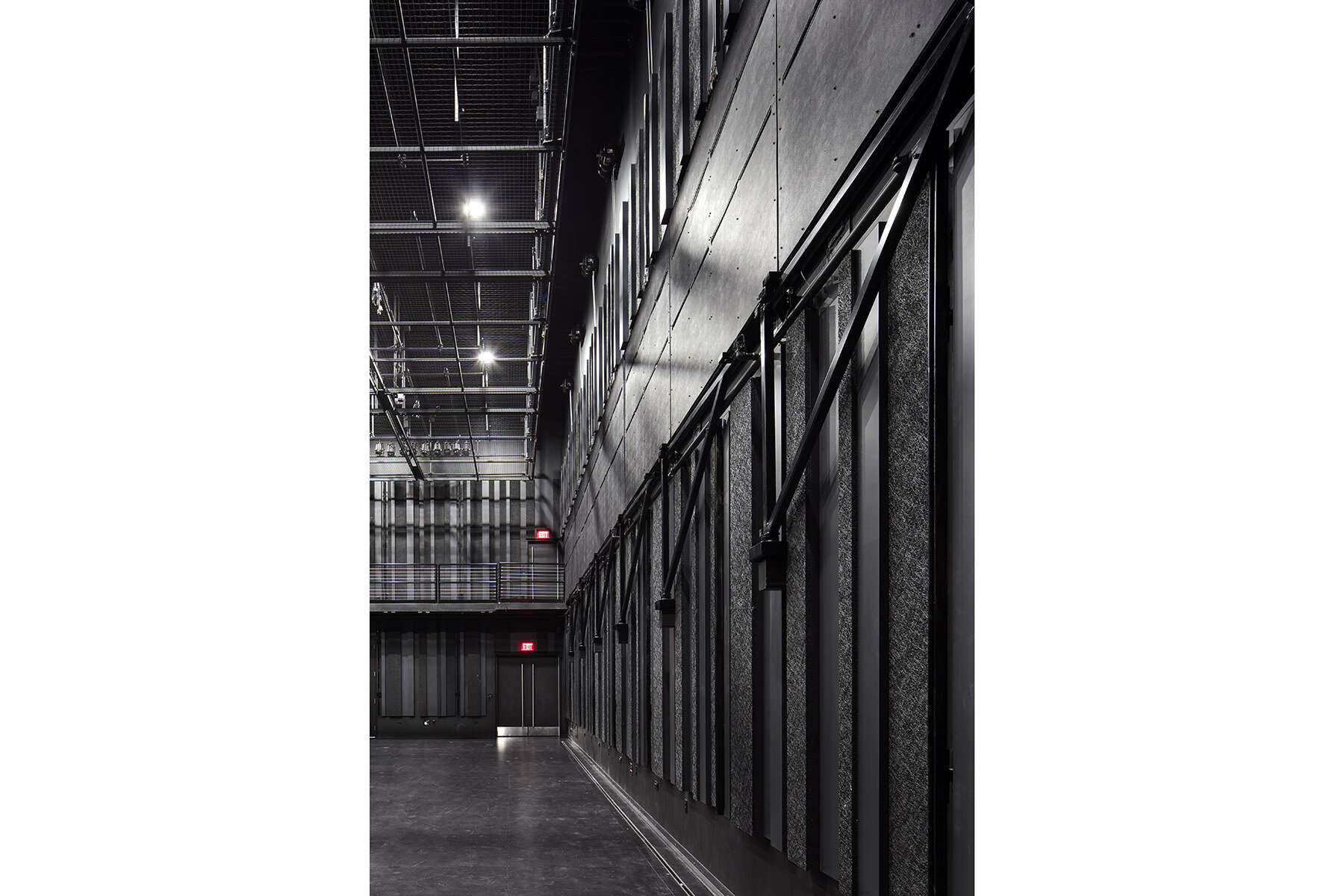

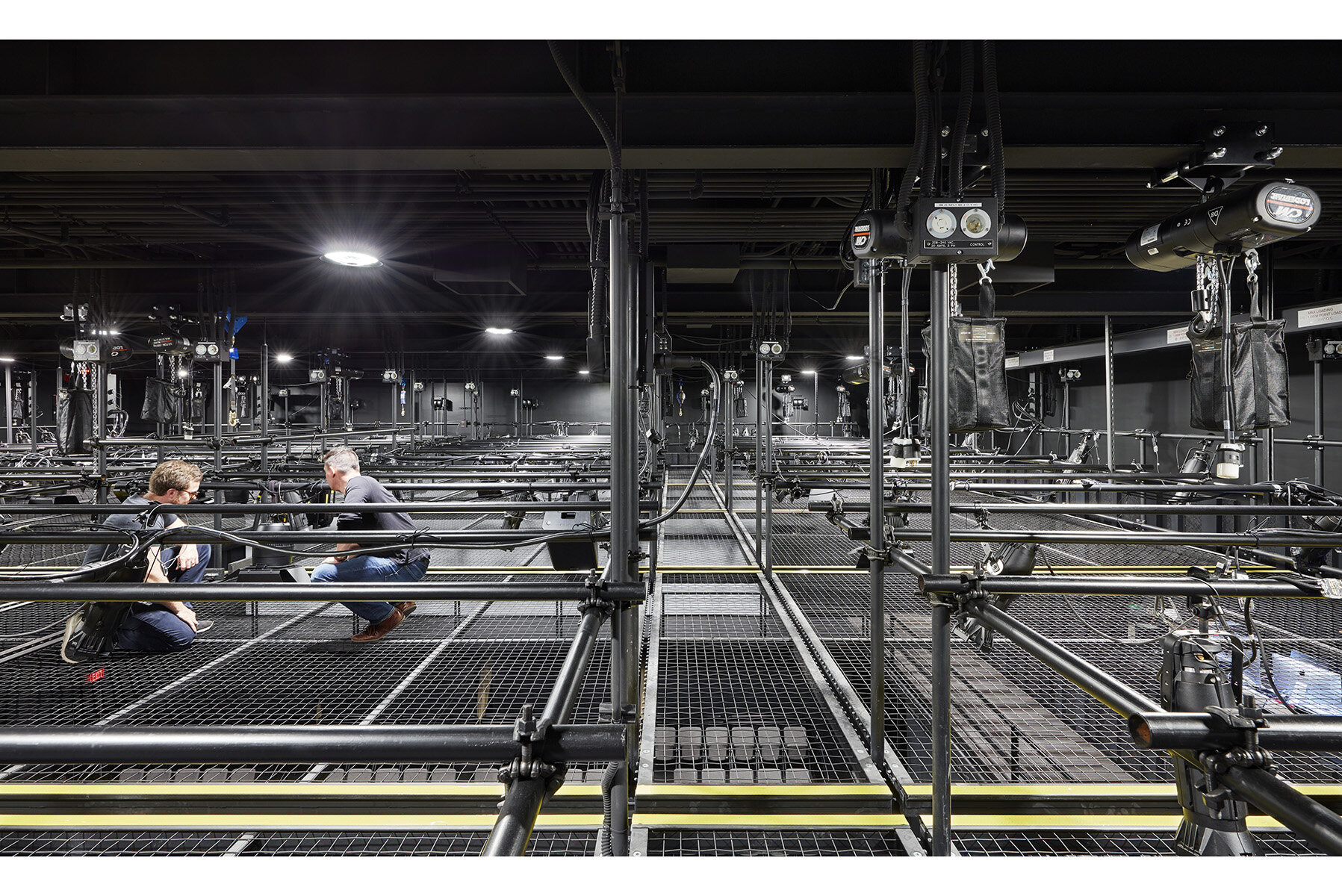

The Music Building and the Arts Commons—now a soaring social hub with clerestory windows, a mezzanine, and an array of seating options—were the first spaces to be completed, in 2012. Two years later, a revamped Studio Arts Building debuted, adding a third floor. In 2019, a completely reimagined Theater Building opened with a highly adaptable black-box space replacing the old proscenium stage. All three phases were designed by HGA, and all three won an AIA Minnesota Honor Award, the state’s most prestigious award for building design.

ENTER visited with David Wheaton, Macalester’s VP of Administration and Finance, to get his perspective on implementing significant capital projects.

As you look back on the decade-long work of transforming the Janet Wallace Fine Arts Center, what learnings or insights leap to mind?

One of the things that is really interesting to me is the point of view of the people who are responsible for the functions and programs in the new space that they will occupy. These campus leaders might be the chair of an academic department or the dean of the faculty if the project is centered on a teaching and learning space; an athletic director if it’s a recreation center; or a residential life director or VP of student affairs if it’s a residence hall or a student center. Most program people, in my experience, do one of these projects in their career. That can cause some of them to think about the design as a way to solve the issues they’ve been having for the last 10 years. So, there can be a backward-looking view, or a bias toward what’s-in-front-of-me-right-now. These are usually the very obvious things that need to be addressed.

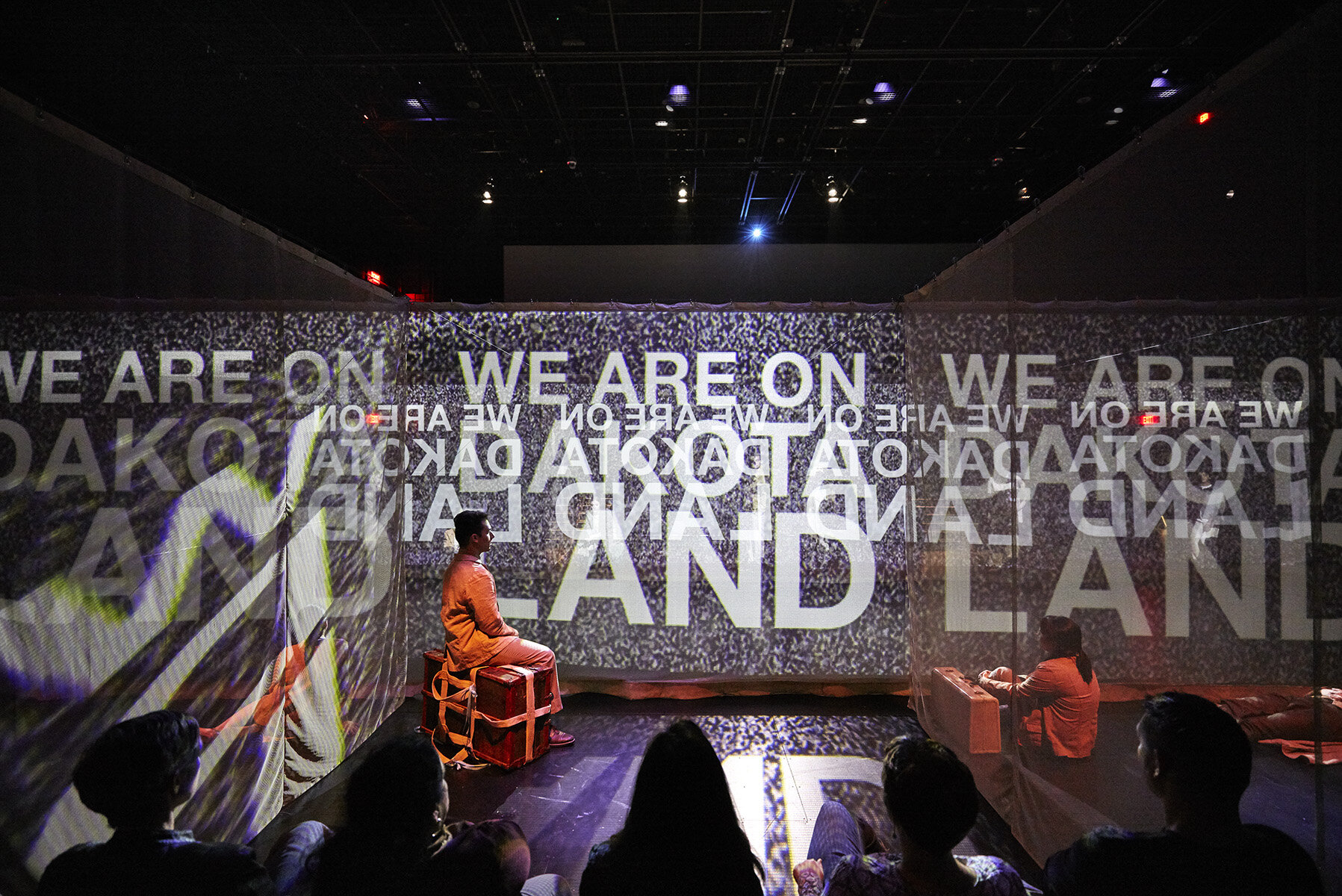

Phase 3 of the Janet Wallace Fine Arts Center transformation houses, among other spaces, the black-box theater, a dance studio/rehearsal space, and classrooms. The highly configurable theater space epitomizes the project’s overall focus on flexibility. Photos by Gaffer Photography.

The architect’s job, in some sense—actually, I sort of feel like this is our job, too, on the facilities and leadership side of the discussion—is to ask, “What might you need in 20 years?” This building is going to last a long time, so let’s make sure we don’t build something that solves all of yesterday’s problems but doesn’t address where we’re going. That’s a hard thing to conceptualize, because most people don’t tend to think out that far. So, the designer’s role in helping push that discussion can make a huge difference in the quality of the project going forward.

* * *

The biggest change I’ve seen in how we’ve approached building projects over the past 15 or so years—outside of sustainable design, which is now routine—is a move away from building extra space into new facilities. The extra space was a little like the contingency in the budget—you knew you would need more space in the future. We now design flexibility into buildings instead. The faculty member who chairs our theater department said it best: Every space in the new theater/classroom wing is designed to do more than just one thing. A performance space doubles as a teaching space. A classroom during the day can host a reception or speaker in the evening using the designated counter and sink space for the requisite pizza delivery.

“Ideally, our design partners are pushing us while they also internalize the problem we’re trying to solve, or the opportunity we’re trying to take advantage of—in other words, they’re listening carefully and reading how much guidance we’re looking for.”

We need to think about what we want to be ready for, even if we don’t choose to put the [accommodation] immediately in place. Here’s an example: At one point, we talked about whether we should have a classroom in the new array that could seat 60 or more students. We don’t typically have classes that big, so we ended up deciding that classes of that type won’t happen often enough for such a space to be useful. But working with HGA, we designed two adjacent classrooms so that, if our programs ever grow in a way that we need a 60-seat classroom, we can take the shared wall out and fix the floor, and we’re set with a larger classroom. We even set up the projectors in each room to face the same direction so that AV setup would work if the wall were removed. It’s really important for owners to get that forward thinking from their design partners.

Like Phase 3, Phases 1 (Music Building and Arts Commons) and 2 (Studio Arts Building) feature a signature facade whose custom architectural expression reflects the arts disciplines housed inside the building. Photos by Paul Crosby.

If you were gifted a consultation with an architect about the Macalester campus, what would you hope to get from them in terms of new ways of thinking or design opportunities?

I think about working with an architect in the same way as I think about working with an attorney, accountant, insurance person, or other outside advisor. Each of them has the experience of working to solve problems for their clients, and each is attuned to new thinking and what is—and isn’t—working in other places. To me, the biggest value our outside partners provide is to bring ideas to us that we may not have thought of, and to ask questions that we’re not asking ourselves. Ideally, they’re pushing us in this way while they also internalize the problem we’re trying to solve, or the opportunity we’re trying to take advantage of—in other words, they’re listening carefully and reading how much guidance we’re looking for.

Of course, the consultation would benefit from a focus on an objective; a random conversation about our facilities wouldn’t be a good use of anyone’s time. Perhaps we’d have the architect come to the campus to talk about our three oldest buildings, or what we’re seeing in our applicant pool and how we should be thinking about that from the point of view of the physical facilities we’re offering. Or, again, what might we need to be thinking about 10 years from now? Because the fact of the matter is, the cycles for design and construction can take up to four or five years, so you can’t just be talking about what is in front of you right now. It’s always worth remembering that projects of this type take multiple years from conception to grand opening. We’re already part of the way into that future state by the time the project is complete.