A Pairing of New Homes Integrates Contemporary, Barrier-Free Design into an Historic Neighborhood

Unique St. Paul residences mark a new chapter for both the owners and the neighborhood they love

By Laurie Junker | June 17, 2021

The two contemporary homes use scale, massing, and materials to fit their historic neighborhood. Photo by Gaffer Photography.

FEATURE

The owners of two new houses in St. Paul didn’t intend to create a case study in bringing universal design to a late-19th-century residential district. They were simply looking for a better living solution for themselves, as they age, and their son, who has developmental disabilities and requires around-the-clock care.

Longtime residents of the Crocus Hill neighborhood, the couple lived in a 100-year-old Tudor that had never been an ideal environment for their son, despite modifications they’d made over the years. Now that he was in his 30s and they themselves were anticipating their own mobility issues, they decided it was time to make a more profound change. Their vision was a fully accessible home with distinct areas—one for them and one for their son and his caregivers—within easy reach of each other. An additional imperative was to stay in the area. “Our previous home wouldn’t work long-term, but we wanted our son to be able to stay in the only neighborhood he’s ever known, close to his activities, among people who watch out for him,” says one of the homeowners.

The parents’ home runs along the street, with views out one end to their son’s home and out the other into bluff-top trees. Photos by Gaffer Photography.

After years of looking, they found an urban unicorn: a house on a triple lot just a few hundred feet away. The home had some serious structural issues and wasn’t particularly attractive, but the couple knew the property was large enough to accommodate the type of living situation they envisioned. They checked with the City of St. Paul and the Heritage Preservation Commission to make sure they could raze the house, purchased the property, and were granted a demolition permit. But the city soon revoked the permit due to opposition from a few neighbors and preservationists, setting into motion months of legal wrangling and stress. “They were just trying to do the right thing for their family—they had no intention of disrupting the neighborhood they lived in and loved themselves,” says Snow Kreilich Architects’ Julie Snow, FAIA. Eventually, the couple prevailed and were able to move forward.

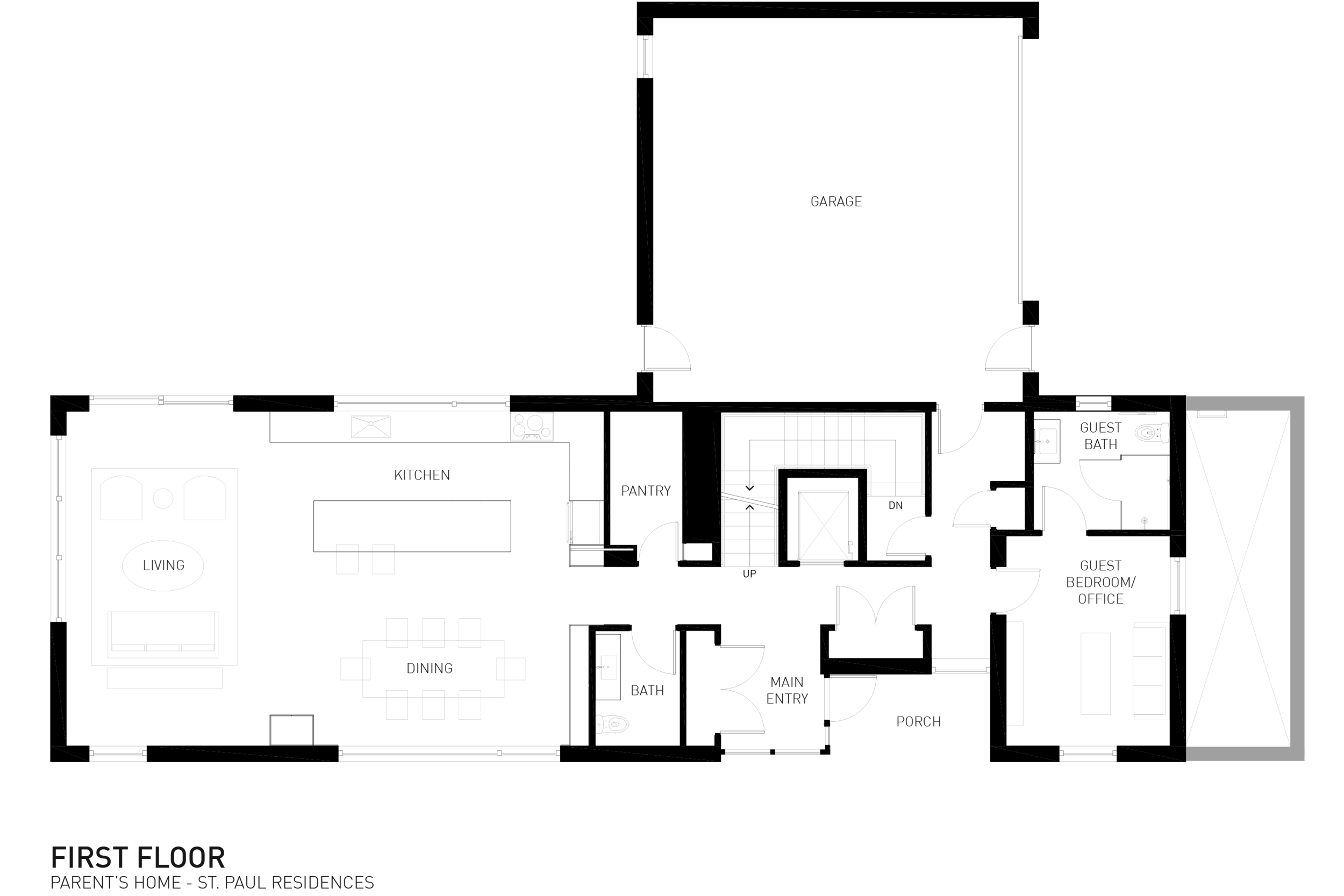

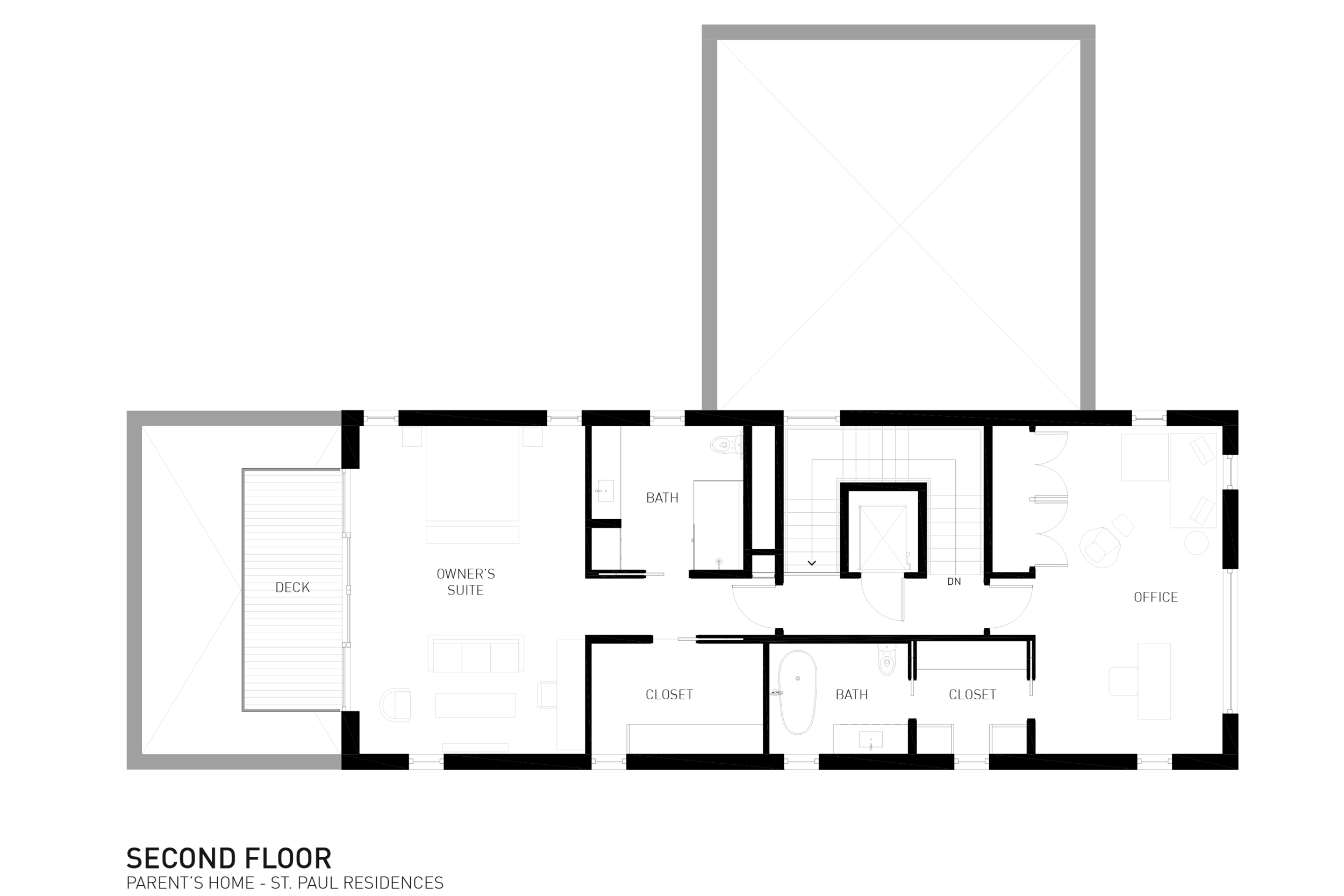

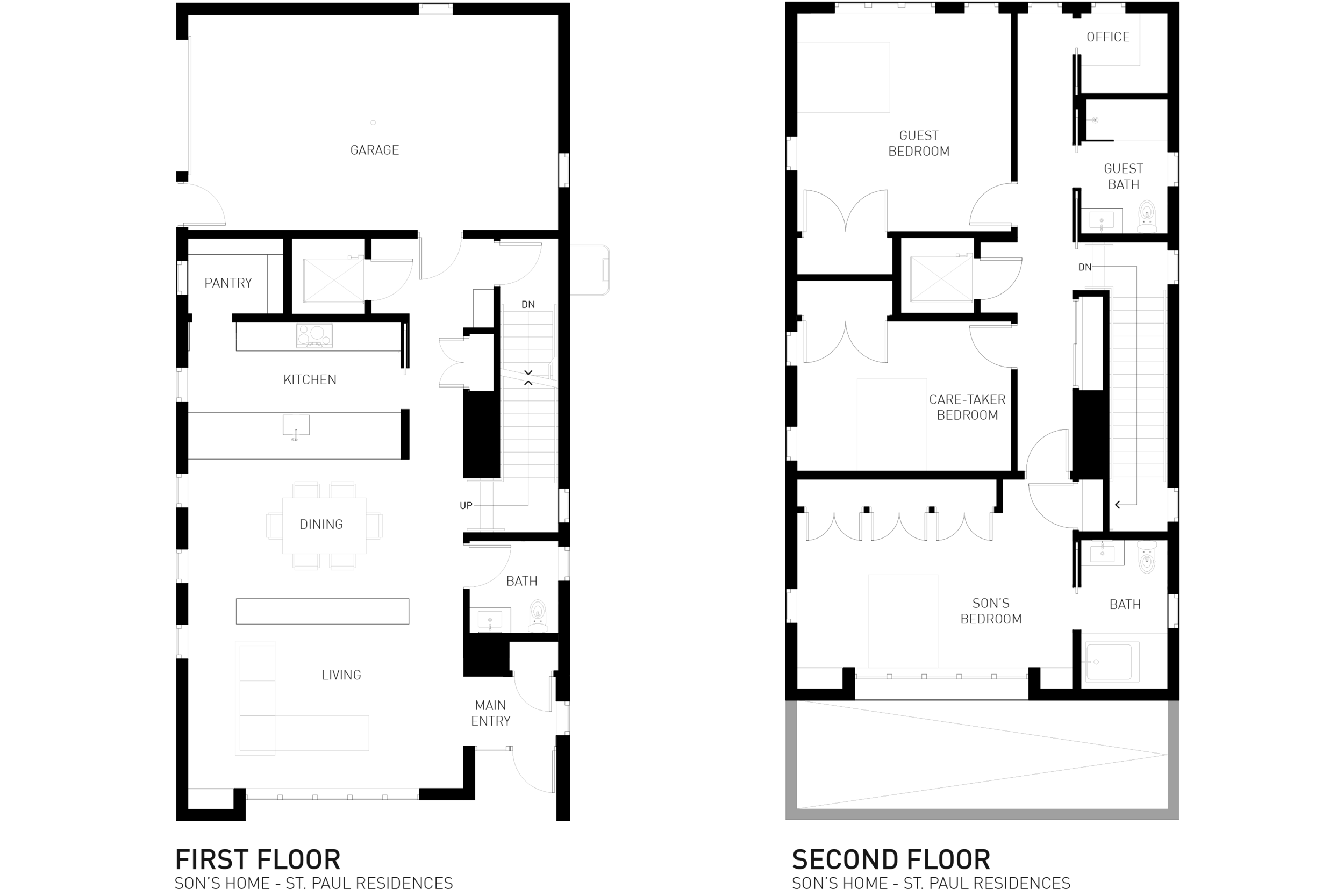

The property was unique for its size and location on a bluff. A site analysis and digital modeling iterations by Snow Kreilich led to a two-residence solution, which the designers believed best suited the neighborhood from a scale and massing standpoint. It also created an opportunity for shared outdoor space. The clients wanted an architecturally significant, contemporary design that would complement, but not mimic, the area’s historic homes.

For Snow Kreilich, a modern home usually means boxy forms, but not in this case. “A flat roof, which is typical of our residential work, didn’t feel right here,” says architect Matt Kreilich, FAIA. “We opted for a more traditional shape and materials considered in a modern way through detailing and proportion in a scale that’s respectful of the neighborhood context.

“This wasn’t solely about finding solutions for our clients’ son. It was also about creating a home that meets their needs now and as they age in place. Barrier-free solutions do just that, as we all deal with mobility issues at various times throughout our lives.”

The thoughtful design employs various techniques to help the residences blend in with their surroundings, including varying the orientation of the two houses. The son’s house is perpendicular to the street, like its next-door neighbor, while the owners’ residence runs along the street, mirroring the house across the way. The two homes are related in appearance but not identical, which helps maintain the varietal flow of the block. Both houses have pitched roofs and framed windows (as opposed to walls of glass) and use traditional materials (stone, copper, stucco, and cedar).

Stone and copper meet midway on the owners’ residence—flush and without any overlayed trim or decorative embellishment to detract from the materials’ richness. The son’s house is stucco with a cedar roof and features a recessed, street-facing patio—a modern interpretation of the front porch. Windows that extend to the floor allow the son to watch the comings and goings of the neighborhood (a favorite activity) and look into his parents’ house across the courtyard, and vice versa. “Having visual communication and being able to see into our son’s house was really important,” says the homeowner, who estimates that she goes back and forth between the houses “about 35 times a day” to prepare food and spend time with her son and his caregivers.

The son’s home features numerous views toward his parents’ house and out to the street, all through windows that extend to the floor. Photos by Gaffer Photography.

Barrier-free design throughout both houses includes wide hallways and doorways, accessible bathrooms, minimal thresholds, and elevators. Specific safety features to mitigate potential hazards for the son include pocket doors to block stairways and access to the kitchen stove. Additionally, the floors are heated and mostly carpeted to make them more comfortable, as he often crawls to get around. The television is placed low to the ground for the same reason. His bedroom is located at the front of the house with a wide view of the street so he can see his caregivers arriving and departing, and the walls have extra soundproofing to help him sleep better.

A key element of the accessibility features is how they’re seamlessly integrated into the design; if you don’t need them, you don’t notice them. “This wasn’t solely about finding solutions for our clients’ son,” says Snow Kreilich’s Tyson McElvain, AIA. “It was also about creating a home that meets their needs now and as they age in place. Barrier-free solutions do just that, as we all deal with mobility issues at various times throughout our lives.”

In late 2020, the two homes were honored with a prestigious AIA Minnesota Honor Award, a program that celebrates achievements in the AIA Framework for Design Excellence. The awards jury recognized the project for its design in three Framework categories: Integration, Well-Being, and Change.

The owners say their new homes have elicited a steady stream of compliments from people in the neighborhood. While that’s been gratifying, they say what really matters is that the houses have helped them achieve their goal. “This whole project was borne out of a desire to have our son firmly and happily established in his own home, with time-tested supports, so that when we die, there are as few transitions [as possible] in his life that will need to take place—for his peace and security.” A plaque they installed in the driveway has the final word:

Neighborhoods are not defined by architectural styles and vocal advocates.

They exist and remain strong by serving the needs of the people who live in them.

These homes were built with love, dedicated to inclusivity, and affirm the right

of people of all abilities to live where they choose.

The St. Paul Residences project team included Snow Kreilich Architects, Streeter Custom Builder, Travis Van Liere Studio, Ericksen Roed & Associates, Pierce Pini & Associates, and James Larson (consulting architect).