Wild Rice Retreat: A Serene Sequel

With a collection of memorable new guest accommodations, the site of a former restaurant in the woods is transformed into a design-forward wellness retreat

By Laurie Junker | May 19, 2022

Treehaus units—Wild Rice Retreat’s largest cabins. Photo by Gaffer Photography.

FEATURE

By all accounts, artist and entrepreneur Mary Hulings Rice was a force of nature. A great granddaughter of the founder of Andersen Windows, Rice gave generously to her adopted hometown of Bayfield, Wisconsin, ran several beloved businesses, and spearheaded popular community events. Her 2020 obituary called her “The Queen of Bayfield.”

One of her best-known ventures was Wild Rice (2001–17), a white tablecloth restaurant a mile out of town on a rocky bluff above Lake Superior. Designed by Salmela Architect’s David Salmela, FAIA, Wild Rice enjoyed both gastronomic and architectural acclaim during its 16-year run; it was a James Beard Foundation semifinalist and received a 2005 AIA Minnesota Honor Award.

“She was a creative lady,” says Salmela, with a smile. “Who builds a restaurant like this in the middle of the woods? But this was Mary’s vision.”

Images 1–6: Inside and out, the 19 cabins immerse guests in the lakeside forest. Photos by Gaffer Photography.

Salmela’s design, a set of connected cedar-clad buildings with gable roofs, was inspired by Scandinavian-flavored boathouses, fishing shacks, and farm buildings in the area. One of the restaurant’s distinctive features—the separation of the dining space and kitchen—was the result of a creative solution to building on what was essentially a pile of rocks. The design housed the dining room in a long, narrow pavilion on piers, nearest the lake, and the kitchen in a parallel pavilion on a traditional foundation, on the inland side. Salmela linked the two via enclosed walkways and two open-air “atria” that allowed the cooks and diners to see each other. “It was a pragmatic decision, but the beauty of it is that you get so much light,” says Salmela. Two decks for outdoor dining were home to the architect’s first “unchimney” (flue-less) fireplaces.

The Sequel

In 2018, after the restaurant closed, the 114-acre property was purchased by Heidi Zimmer, a real estate developer with experience in creating live/work spaces for artists. She, too, had a vision. “I wanted to create a retreat that weaved together creative expression and health and wellness,” she says.

“We’ll let the wood age like old buildings in Norway. The contrast between the aging and the painted wood enhances both.”

To develop a new master plan that added guest accommodations and a few additional buildings for yoga and sauna/meditation, Zimmer turned to Salmela and landscape architect Travis Van Liere, who nearly 20 years earlier had led the Coen + Partners site design for Wild Rice. The team’s initial vision for modular camper-cabins soon morphed into a plan for cabins with creature comforts that offer guests an inviting experience year-round. Salmela designed three lodging options: RicePod (sleeps up to two), Nest (up to four), and Treehaus (four to eight). Each unit has a kitchenette, bathroom, and heated floors or baseboard heat.

The original buildings now serve as the Retreat Center, with guest check-in, a gift shop, and a multipurpose space for activities and events in the former dining space and the new NOVO restaurant in the adjacent pavilion.

For more information on Wild Rice Retreat lodgings, dining, and personal and guided retreats, visit wildriceretreat.com.

Order and Calm

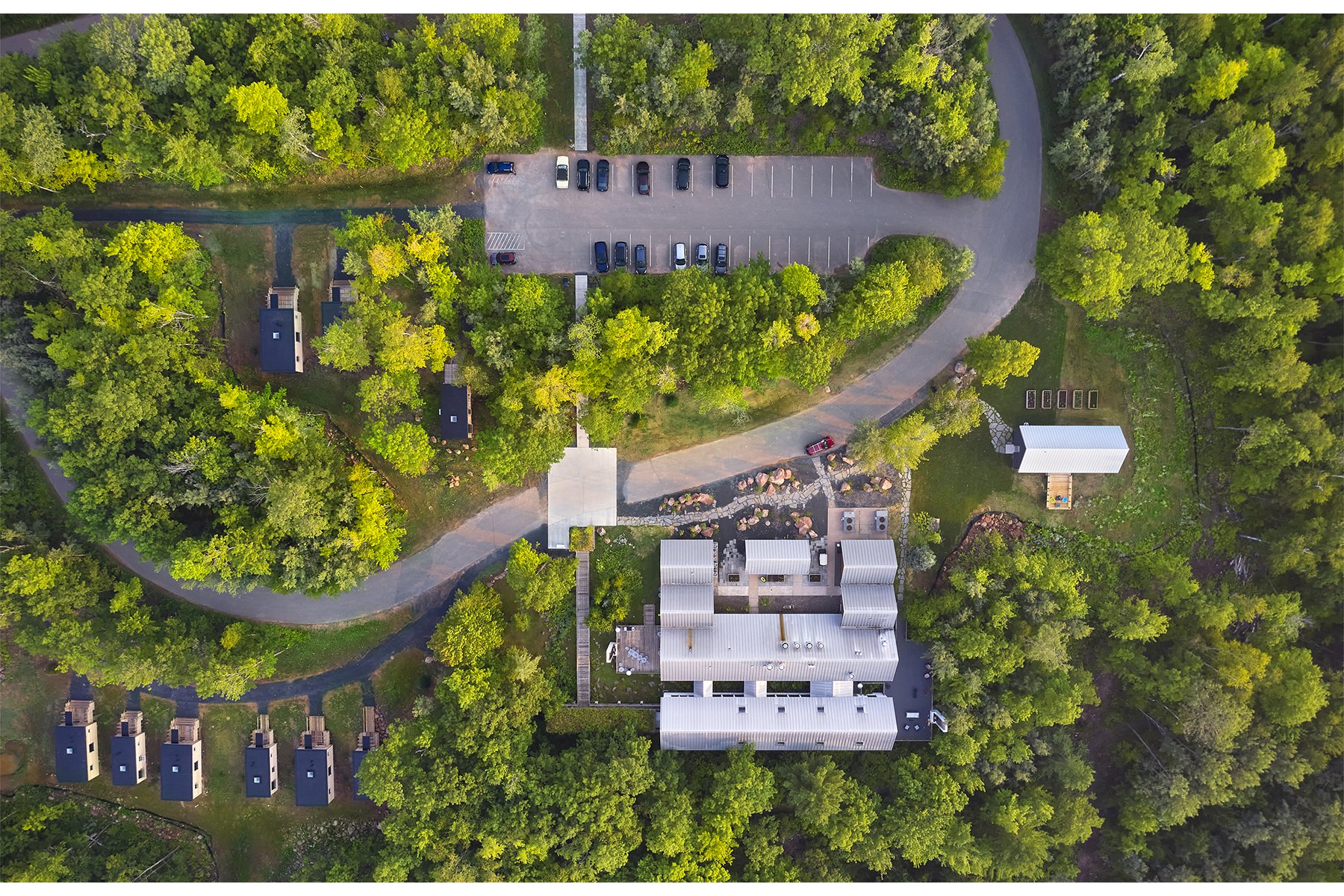

The 19 cabins are clustered near the Retreat Center rather than scattered throughout the property. The arrangement makes practical sense for utility lines and housekeeping and leaves most of the woods intact. It also offers something intangible. “David felt strongly about doing it this way,” says Zimmer. “I wasn’t sure at first, but there’s an orderliness about it that gives people comfort as they move around the site. It balances the wildness of the woods.”

Images 1–6: The former restaurant, with its wooden bridge entry walk, is now the Retreat Center. Architect David Salmela also designed new buildings for yoga and sauna/meditation. Photos by Gaffer Photography.

The cabin interiors are lined in locally sourced basswood—Zimmer wanted the warmth and texture of wood, but not pine—with contrasting black slate floors. All of the units feature a skylight overhead and windows on all four sides, strategically placed to maximize natural light and views while still providing privacy. Each unit also has a balcony or porch to invite casual interactions and cultivate a sense of community.

To accentuate the cabins’ modern lines, Salmela kept the exterior palette simple with sustainable black Richlite cladding and cedar lap siding. “We’ll let the wood age like old buildings in Norway,” he says, noting that the painted portions on the larger cabins are on the lower half of the structures, making them easier to maintain. “The contrast between the aging and the painted wood enhances both, and no one needs to get on a ladder to touch up the paint.”

For the landscape, Van Liere tapped into the original site design, extending pathways to reach the cabin groupings and the sauna and yoga buildings. Ferns, sedges, and evergreen trees were dug up from the vast woods and replanted around cabins and pathways. Glacial rocks unearthed during construction now define walkways in sculptural arrangements throughout the grounds. “We wanted everything to look like it’s always been there,” says Van Liere.

Retreat guests are responding to the design. “They tell me they gazed out the window at the beautiful lake and woods and rested for the first time in years,” says Zimmer. Salmela, who has revisited other past projects over the years, says Wild Rice holds a special place in his heart: “There’s a cultural rootedness here that Mary and Heidi intuitively understood, and we strove to be worthy of it.”

The Wild Rice Retreat project team included Zimmer Development, Salmela Architect, TVL Studio, Kraus-Anderson, Charlestowne Hotels, and BKV Group.